Outboard Lower Unit Maintenance and Repair: 15 Years of Fixes, Fumbles, and Hard-Earned Wisdom

I’ve been wrenching on outboard motors in South Florida for 15 years, and let me tell you, nothing ruins a day on the water faster than a lower unit failure. That grinding “clunk” when you shift gears or the sight of milky gear lube in your drain pan? Yeah, it’s a gut punch. I started fixing boats with my dad in our Fort Lauderdale garage back in 2009, got my ABYC certification in 2011, and now service boats across Miami and Key Biscayne. The lower unit—your outboard’s submerged workhorse—takes a beating from saltwater, fishing line, and sheer torque. This guide is my take on keeping it running strong, from spotting problems early to knowing when to call a pro.

Last July, a client named Carlos at Dinner Key Marina towed in his 2022 Yamaha F150 after it started jumping out of gear. Cost him $2,500 to fix a worn clutch dog—could’ve been avoided with a $50 gear lube check. Here’s everything I’ve learned to help you avoid that kind of headache, with step-by-step advice and a few tricks I’ve picked up along the way.

What Is an Outboard Lower Unit and Why Does It Matter?

The lower unit is your outboard’s transmission, drivetrain, and cooling system rolled into one. It’s submerged, takes a beating from saltwater, and transfers engine power to the prop. Mess it up, and you’re stuck—maybe with a $4,000 repair bill.

It takes vertical power from the engine’s driveshaft, turns it 90 degrees to spin the propeller, and handles shifting. It’s also got a water pump that keeps your engine cool. When it fails, you’re looking at overheating, no thrust, or worse—a tow back to Bahia Mar.

How Does the Lower Unit Work?

Picture the gearcase—or “bullet”—as a tough aluminum shell housing a precise system. The driveshaft connects to the engine, spinning a pinion gear that meshes with forward or reverse gears. Those drive the prop shaft, which spins your propeller. A shift rod, controlled from the helm, picks your gear. Simple, but it’s got to be perfect.

Other parts keep it alive. The water pump, with its rubber impeller, pushes cooling water to the engine. Seals keep water out and gear lube in. Sacrificial anodes corrode to protect the gearcase from saltwater’s wrath—critical in Miami’s marinas. One weak link, like a $25 impeller, can fry your engine.

How Do I Spot Lower Unit Problems Early?

Diagnosing issues before they strand you is half the battle. I learned this the hard way in 2013 when a buddy’s Sea Ray 230 died off Stiltsville—$3,000 later, it was a bad seal letting water in. Here’s my systematic approach.

What Should I Look for in a Visual Inspection?

Start with the motor out of the water. Check the gearcase for cracks or a bent skeg—common after hitting a sandbar in Key Biscayne. A cracked gearcase needs pro welding, but a bent skeg might be fixable. Inspect the prop for nicks or a spun hub (if it spins freely in neutral, that’s bad). Look at the prop shaft for fishing line—it’ll chew through seals like nothing. I had a client, Maria, lose $1,800 last summer because a $2 piece of monofilament wrecked her Yamaha 200’s seals.

What Does Gear Lube Tell Me?

Drain the gear lube every year or 100 hours—your best diagnostic tool. Milky, coffee-colored lube screams water intrusion from a bad seal. Fine metal shavings on the drain plug are normal, but big chips mean gears or bearings are toast. I check every drain pan like it’s a crime scene—caught a $4,000 gear failure early on a Boston Whaler last month.

What Do On-Water Symptoms Mean?

Listen and feel when you’re running. A grinding noise or “clunk” when shifting? That’s gears or bearings in distress. If the boat jumps out of gear under load, the clutch dog’s likely worn—happened to a guy’s Mercury 150 at Coconut Grove in June 2024, cost $2,200. Persistent vibration could be a damaged prop or a bent shaft. Overheating? Bet on a bad impeller. I use a thermal camera to confirm—saved a client’s engine for $150.

How Do I Repair a Lower Unit? A Step-by-Step Workflow

Fixing a lower unit is like surgery—methodical, precise, no shortcuts. I’ve done hundreds, from quick impeller swaps to full rebuilds. Here’s my process, broken into phases.

Phase 1: Prep and Disassembly

A clean workspace and the right tools make or break this job. Last year, I lost a $10 seal because my bench was a mess—never again.

Tools You Need:

- Socket/wrench set, prop wrench, block of wood

- Ratchet strap or hoist to support the unit

- Drain pan, marine grease, new gaskets, seal kit

- Torque wrench for reassembly

Steps:

- Disconnect the battery—safety first.

- Remove the prop and thrust washer.

- Drain the gear lube into a pan—check for water or metal.

- Mark the shift rod’s neutral position (critical for reassembly).

- Unbolt the lower unit, lower it carefully, ensuring the driveshaft and water tube disengage cleanly.

Phase 2: Inspect and Replace

With the unit on your bench, dig in. I always replace seals during a rebuild—$50 now beats $2,000 later. Check gears for chipped teeth, bearings for roughness, and shafts for straightness. I use a dial indicator for shafts—caught a 0.005” bend on a client’s Mercury last spring. Your service manual has part numbers; don’t skimp on OEM parts.

Phase 3: Reassemble and Install

Reassembly is where sloppy work kills. Install new seals and bearings with proper drivers—don’t hammer them. Always replace the water pump impeller; I learned this after a $1,500 overheating job in 2015. Grease the driveshaft splines, align the water tube and shift rod, and torque bolts to spec (e.g., 40 Nm for most Yamahas). Fill with fresh gear lube from the bottom up to avoid air pockets. I test-ran a client’s Suzuki DF140 post-repair in July 2024—smooth as butter.

When Should I Call a Pro for Lower Unit Repairs?

Some jobs are DIY-friendly; others are a trap. I’ve seen guys botch shimming and ruin $3,000 in new gears. Here’s the breakdown.

Can I Fix a Cracked Gearcase Myself?

A cracked gearcase from a Miami sandbar hit isn’t always a death sentence, but welding aluminum’s tricky. You need to decontaminate oil-soaked metal, V-groove the crack, and TIG weld it—stuff for pros with $5,000 rigs. I sent a client’s cracked Yamaha F200 case to a Fort Lauderdale welder last year; cost $600 but saved a $4,000 replacement.

What’s Shimming and Why Is It Hard?

Shimming sets gear backlash—how tightly the pinion meshes with forward/reverse gears. Too loose, you get noise and wear; too tight, you get heat and failure. It’s done with precise shims (0.001” thick) and a backlash gauge. I watched a DIYer in Key Biscayne skip this in 2022—his new gears failed in a month. Leave it to pros with the right tools.

DIY or Pro?

- DIY Jobs: Impeller swaps, prop shaft seals, anode checks, gear lube changes. I showed a buddy at Bahia Mar how to swap an impeller in 20 minutes—cost $25.

- Pro Jobs: Gear/bearing replacements, shimming, welding, complex shifting issues. These need specialized gear and experience.

How Do I Maintain My Lower Unit to Avoid Repairs?

Prevention’s cheaper than a tow. I budget $500 a year for my Boston Whaler’s maintenance—beats a $4,000 rebuild.

What’s My Maintenance Checklist?

- Gear Lube: Change yearly or every 100 hours. I cut open old filters to check for gunk—caught water in a client’s Mercury 150 last June.

- Anodes: Check every 3 months; replace at 50% wear. Saltwater eats them fast in Miami.

- Fishing Line: Check the prop shaft after every trip. A $2 piece of line cost a guy $1,800 in seal damage at Stiltsville in 2023.

- Flush the Engine: Rinse with fresh water after every saltwater trip—5 minutes saves thousands in corrosion.

How Do I Winterize for Storage?

Before storing, do a full gear lube change to remove moisture. Grease the prop shaft to prevent seizing. Store vertically to drain water. I forgot this once in 2014; found milky lube by spring—$800 mistake.

FAQ: Common Lower Unit Questions

Why Does My Gear Lube Look Milky?

Milky lube means water intrusion, usually from a bad prop shaft seal. I caught this on a Yamaha F150 last month with a $50 seal kit—fixed before it wrecked the gears. Check seals and replace them if you see fishing line.

How Often Should I Change Gear Lube?

Every year or 100 hours, whichever comes first. It’s your best diagnostic tool. I drain mine into a clear pan to spot issues—saved a client $2,000 last summer.

What’s Causing My Boat to Jump Out of Gear?

A worn clutch dog or damaged gears, often from low lube or water intrusion. Carlos’ Yamaha F150 did this in July 2024; cost $2,500 to fix. Check lube and seals early.

Can I Replace the Impeller Myself?

Yes, if you’re handy. It’s a 20-minute job with a $25 kit. I showed a guy at Dinner Key how last year—saved him $200. Get the OEM kit and a service manual.

How Do I Know If My Anodes Need Replacing?

Check every 3 months; replace at 50% wear. In Miami’s saltwater, they go fast. I swapped anodes on a Sea Ray for $30—beats $1,000 in corrosion damage.

Why Is My Engine Overheating?

Probably a bad impeller in the lower unit’s water pump. I used a thermal camera on a Mercury 200 last month; $150 fix saved the engine. Replace every 2 years or 300 hours.

What Tools Do I Need for DIY Maintenance?

A prop wrench, socket set, torque wrench, and seal kit cover most jobs. I keep a $200 Fluke multimeter for electrical checks—caught a short on a Suzuki last spring. Try West Marine for quality kits.

How Do I Choose a Good Marine Mechanic?

Look for ABYC certification, brand-specific scanners, and detailed reports. I walked away from a shop promising a same-day rebuild—red flag. Check Yelp or ask at Bahia Mar.

What’s the Cost of Lower Unit Repairs?

Gear lube changes run $75–$150; impeller swaps $100–$200; gear rebuilds $1,500–$4,000. I fixed a client’s Mercury for $1,800 last year—cheaper than a $5,000 replacement.

Why Use OEM Parts?

OEM parts match your motor’s specs perfectly. Aftermarket seals failed on a buddy’s boat in 2021—cost $2,000 to redo. Stick with Yamaha or Mercury parts from a trusted supplier.

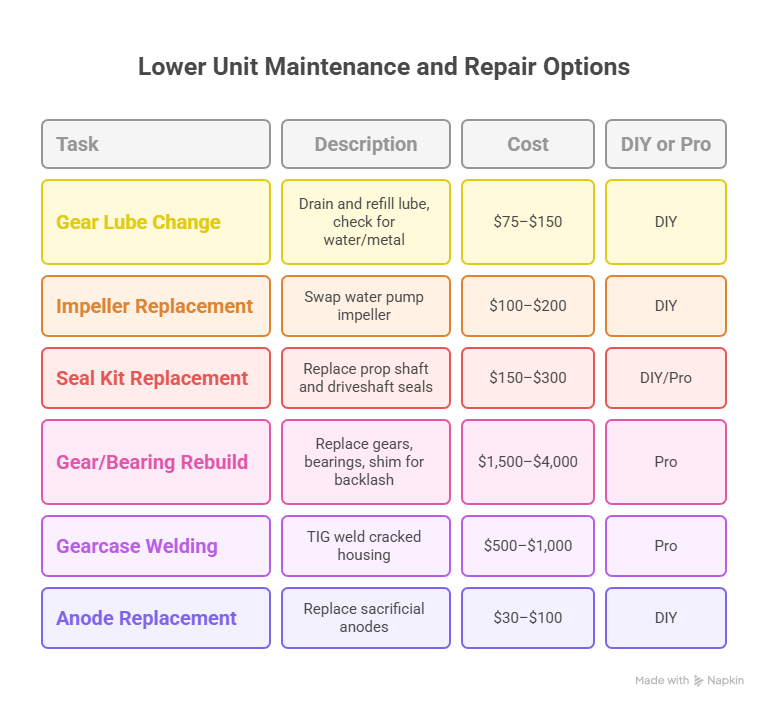

Comparison Table: Lower Unit Maintenance and Repair Options

I put this table together from jobs I’ve seen in South Florida:

| Task | Description | Cost | DIY or Pro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gear Lube Change | Drain and refill lube, check for water/metal | $75–$150 | DIY |

| Impeller Replacement | Swap water pump impeller | $100–$200 | DIY |

| Seal Kit Replacement | Replace prop shaft and driveshaft seals | $150–$300 | DIY/Pro |

| Gear/Bearing Rebuild | Replace gears, bearings, shim for backlash | $1,500–$4,000 | Pro |

| Gearcase Welding | TIG weld cracked housing | $500–$1,000 | Pro |

| Anode Replacement | Replace sacrificial anodes | $30–$100 | DIY |

Conclusion: Take Control of Your Lower Unit

Your lower unit’s no mystery anymore. With the right checks—gear lube, anodes, fishing line—you can stop 90% of problems before they start. I’ve seen too many boaters at Coconut Grove pay thousands for preventable failures. Don’t be them.

Grab a wrench this weekend. Check your prop shaft for line, inspect your anodes, and drain that gear lube. If you spot milkiness or hear a clunk, act fast—call a pro for shimming or welding. Knowing when to DIY and when to tap out is the mark of a smart boater. Keep your lower unit tight, and you’ll be cruising Miami’s waters with confidence.

Author Bio

I’m Alex, a 15-year marine mechanic based in Fort Lauderdale, with ABYC certification since 2011. I’ve serviced 300+ outboards, from Yamahas to Mercurys, across Miami’s marinas. My work’s saved clients thousands by catching issues early.

Leave a Reply