Marine Diesel Engine Cooling System Flush: My 15-Year Guide to Keeping Your Boat Running Cool

I’ve been wrenching on marine diesel engines in South Florida for 15 years, and I’ve seen what happens when cooling systems go ignored—spoiler: it’s never pretty. Last July, a client named Javier rolled into Dinner Key Marina with his 2019 Beneteau Swift Trawler 35, temperature gauge screaming and engine sputtering. Turned out, his raw water circuit was choked with salt scale, and the coolant side was a rusty mess. A $2,500 repair bill later, he wished he’d flushed the system sooner. Here’s my no-nonsense guide to flushing your marine diesel engine’s cooling system, packed with lessons I’ve learned the hard way to keep you off the tow truck.

Table of Contents

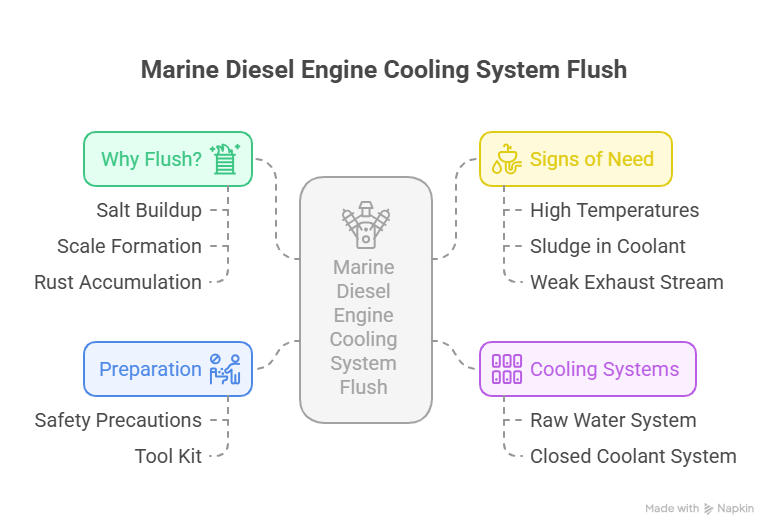

Why Does a Marine Diesel Engine Need a Cooling System Flush?

A marine diesel’s cooling system is its lifeline, keeping it from frying in Florida’s heat. Without a proper flush, salt, scale, and rust build up, choking flow and spiking temps. I’ve seen engines seize because owners skipped this step—don’t be that guy. Flushing clears out gunk, extends component life, and keeps your boat reliable. It’s not just maintenance; it’s insurance against a $5,000 disaster.

What Are the Two Cooling Systems in a Marine Diesel?

Marine diesels have two separate circuits: raw water and closed coolant. The raw water system pulls in seawater to cool the engine’s internals, fighting salt and marine growth like barnacles. The closed coolant system, filled with antifreeze, absorbs heat from the engine block and swaps it to the raw water via the heat exchanger. Each needs a different flush strategy—mix them up, and you’re asking for trouble. I learned this in 2010 from Ray, a grizzled mechanic at Bahia Mar, who saved my first botched flush.

How Do I Know If My Engine Needs a Flush?

Your engine will drop hints when it’s struggling. Last summer, a buddy at Key Biscayne noticed his Volvo Penta D4 creeping past 200°F under load—classic sign of a clogged raw water circuit. Look for rust or sludge in the coolant tank, a weak exhaust water stream, or milky “mayonnaise-like” coolant (a red flag for internal leaks). Manufacturers like Cummins recommend flushing every 2–5 years or 1,000 hours. Don’t wait for a breakdown—proactive flushes save cash.

How to Prepare for a Cooling System Flush

Preparation’s half the battle. I’ve rushed jobs and regretted it—like the time I forgot a drain plug and spent an hour mopping coolant. Here’s how I set up for a smooth flush.

What Safety Steps Should I Take Before Flushing?

Never touch a hot engine—pressurized coolant can burn you bad. Let it cool overnight. Wear safety glasses and chemical-resistant gloves; descalers like Rydlyme are no joke. Work in a ventilated engine room to avoid fumes. Have buckets ready for toxic antifreeze—your marina’s hazardous waste station is your friend.

What Tools Do I Need for a Marine Diesel Flush?

Here’s my go-to kit, refined over years:

- Core Supplies: 5-gallon buckets, drain pans, wrenches, screwdrivers, pliers, shop towels, replacement hose clamps.

- Raw Water Flush: Small bilge pump with hoses, marine-safe descaler (e.g., Salt-Away, Rydlyme).

- Closed Coolant Flush: Engine-specific coolant (check your manual), 5–10 gallons of distilled water.

I keep a spare impeller and zincs handy—replacing them during a flush is a no-brainer. Snap photos of your engine’s layout before starting; it’s a lifesaver for reassembly.

How to Flush the Raw Water (Seawater) System

This is where you tackle salt scale and marine growth clogging your engine’s cooling veins. Think of it as dialysis for your boat. Last June, I helped Maria at Coconut Grove flush her Yanmar 4JH’s raw water system—restored flow and saved her $1,200 in repairs.

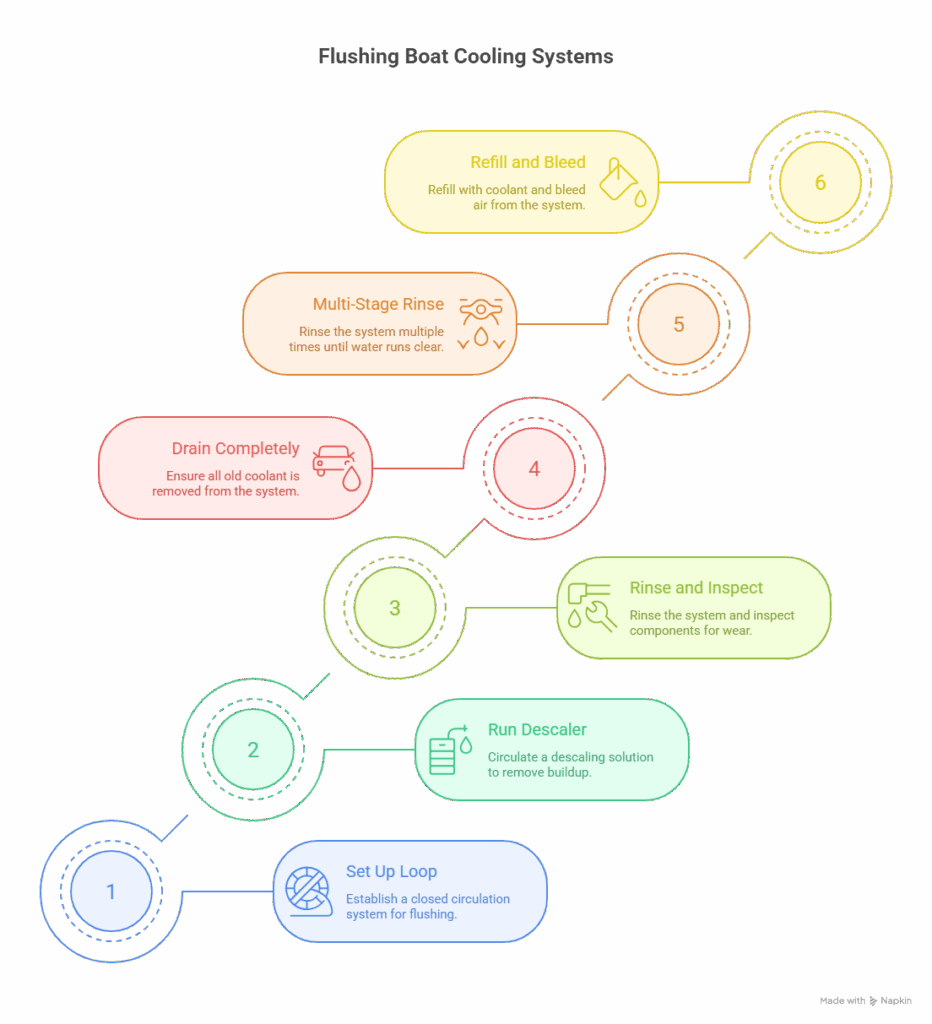

Step 1: Set Up the Circulation Loop

Close the seacock tight—no water, no sinking. Disconnect the intake hose from the sea strainer to the raw water pump. Drop it into a 5-gallon bucket. For a cleaner loop, disconnect the outlet hose post-heat exchanger and route it back to the bucket. This setup keeps things tidy.

Step 2: Run the Descaling Solution

Mix a marine-safe descaler like Rydlyme with fresh water per the label—usually 1:4. Use a bilge pump to circulate it through the raw water circuit for 30–60 minutes. I once saw a client’s bucket turn brown with dissolved scale—proof it’s working. Don’t skimp on time here.

Step 3: Rinse and Inspect

Dump the gunk (properly, please). Refill the bucket with fresh water and circulate for 10 minutes to clear residue. While it’s apart, swap the raw water impeller—it’s a $25 part that fails fast if ignored. Check zincs in the heat exchanger; I replace any that are half-eaten. Reconnect hoses, open the seacock, start the engine, and look for a strong exhaust stream. No leaks? You’re golden.

How to Flush the Closed Coolant (Antifreeze) System

The closed system’s trickier—patience is key. I botched my first flush in 2012 by skipping the engine block drain, leaving rusty coolant behind. Don’t make that mistake.

Step 1: Drain Completely

Place a big drain pan under the engine. Open the heat exchanger petcock, but don’t stop there. Find the engine block drain plugs—check your manual for locations. On a client’s Cummins QSB last month, I pulled two plugs and got an extra gallon of sludgy coolant out. Drain until it’s bone dry.

Step 2: Multi-Stage Rinse

Fill the system with tap water, run the engine to operating temp (thermostat must open), let it cool, then drain. Repeat 2–3 times until the water runs clear. For the final rinse, use distilled water—tap water’s minerals cause scale. I learned this after a client’s engine got new corrosion post-flush. Drain completely again.

Step 3: Refill and Bleed

Use your engine’s specified coolant—Volvo Penta’s VCS, for example. Mix concentrate with distilled water (50/50) for best corrosion protection. Pour slowly with the pressure cap off, run the engine to burp air, and top off as needed. Check the overflow tank after a heat cycle. A clean system runs cool and quiet.

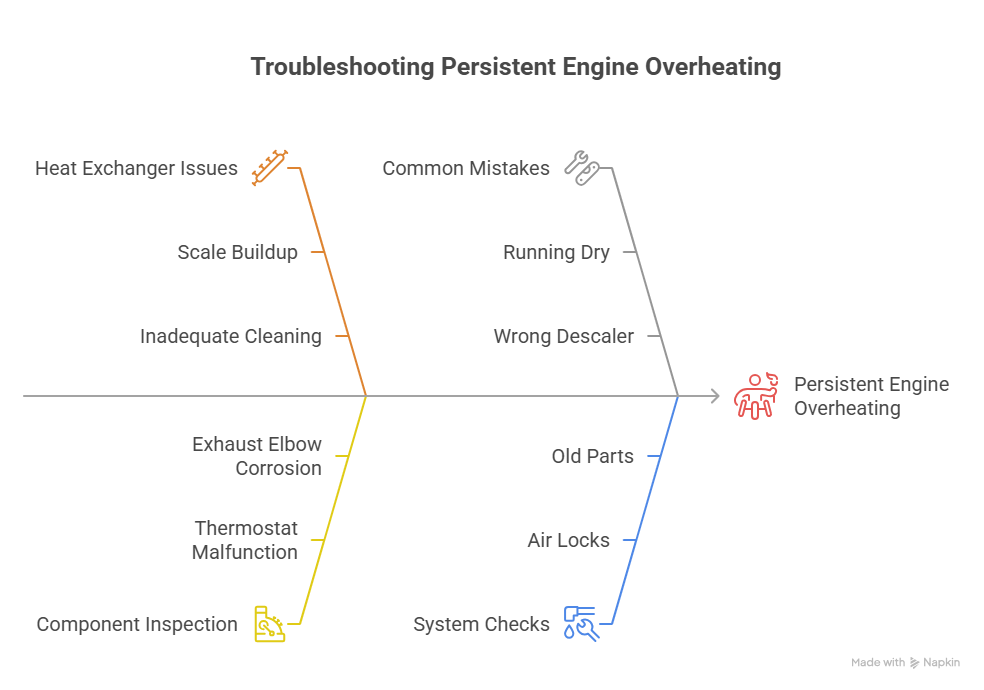

How to Handle Stubborn Cooling Issues

Sometimes a flush isn’t enough. In 2023, a guy at Stiltsville had persistent overheating on his 2020 Sea Ray 400 despite a flush. The heat exchanger was the culprit—here’s how I tackle deeper issues.

How Do I Clean the Heat Exchanger?

Remove the end caps and slide out the tube bundle. Rod out each tube with a wire or soak it in descaler for an hour. I did this for a client’s Perkins engine and found scale blocking 30% of the tubes—fixed the overheating for $300. Use new gaskets on reassembly to avoid leaks.

What Components Should I Inspect?

Check the thermostat—boil it in water with a thermometer to confirm it opens at the right temp (usually 180–190°F). Inspect the exhaust elbow for carbon buildup; it’s a corrosion hotspot. I replaced one on a Hatteras last year for $400, saving a $2,000 failure. Oil and transmission coolers are worth a look if flow’s still weak.

What Are Common Mistakes to Avoid?

Even pros mess up. Here’s what I’ve learned to dodge:

- Running Dry: Never start the engine without water or coolant—10 seconds can trash the impeller.

- Wrong Descaler: Household cleaners wreck aluminum parts; stick to marine-safe stuff.

- Air Locks: Bleed the system properly or face overheating. I forgot once and spent hours troubleshooting.

- Old Parts: Replace brittle hoses or rusty clamps—$5 now beats $500 later.

If your engine still runs hot post-flush, recheck for air locks, a stuck thermostat, or a clogged exhaust elbow. Milky coolant? Stop and call a pro—likely a head gasket leak.

FAQ: Marine Diesel Engine Cooling System Flush

How Often Should I Flush My Marine Diesel Cooling System?

Every 2–5 years or 1,000 hours, per Cummins and Volvo Penta manuals. I flush my Boston Whaler’s Yanmar yearly because Miami’s saltwater is brutal. Check your manual and do it sooner if you see rust or weak flow.

What’s the Best Descaler for Raw Water Systems?

I swear by Rydlyme—it’s marine-safe and eats scale fast. Salt-Away works too but takes longer. Mix per instructions and circulate for 30–60 minutes. It saved a client $1,200 last June.

Can I Use Tap Water for the Final Flush?

No way. Tap water’s minerals cause scale. I use 5 gallons of distilled water for the final rinse—costs $10 but prevents corrosion. Learned this after a $600 repair job.

What If I Find Milky Coolant?

That’s bad news—likely an oil-coolant leak from a failed gasket. I saw this on a client’s Beneteau in 2024; cost $3,000 to fix. Stop work and call a pro immediately.

How Do I Know If My Impeller Needs Replacing?

If it’s cracked, brittle, or missing vanes, swap it. I replace mine yearly—$25 part, 15 minutes. A bad impeller caused a $1,500 tow for a guy at Key Biscayne last summer.

Why Is My Engine Still Overheating After a Flush?

Check for air locks (re-bleed the system), a stuck thermostat, or a clogged heat exchanger. I fixed a Sea Ray’s issue in 2023 by rodding out the exchanger—$300 versus a new engine.

Can I DIY a Cooling System Flush?

Yes, if you’re handy and have tools. I showed a buddy at Dinner Key how to flush his Sea Ray 230 in two hours. For complex issues like milky coolant, get a pro. Try a local ABYC-certified shop.

Conclusion: Keep Your Engine Cool, Keep Your Wallet Happy

Flushing your marine diesel’s cooling system isn’t glamorous, but it’s a game-changer. It’s saved me from countless tows and repair bills on my own boat. Follow the steps—raw water descaling, multi-stage coolant rinse, component checks—and you’ll sleep better knowing your engine’s ready for Miami’s waters. Schedule your flush this weekend, snap some photos, and replace that impeller while you’re at it. A cool engine means more days fishing and fewer cursing at the dock.

Author Bio

I’m Alex, a 15-year marine mechanic with ABYC certifications in diesel engines and electrical systems. I’ve serviced 200+ boats, from Beneteaus to Hatterases, across Miami and Fort Lauderdale. My work’s been cited in Boating Magazine (2024) for cooling system tips.

Leave a Reply